Knowit Experience

By connecting data and insights to creativity and technology, we create customer experiences and robust solutions centered around the user. Design, development of digital products and platforms, brands, marketing, e-commerce, and data analytics are our primary expert areas.

We are usually on site with our clients in our assignments, to support them and have a presence nearby. Sometimes we perform projects in-house. We have a strong local presence and are happy to collaborate across national borders, to create the best solutions and experiences.

Cross-functional and agile

In agile and cross-functional teams, we deliver digital customer experiences through web applications, app solutions, communications concepts, and innovative solutions that contribute to simplifying everyday life for people and strengthening bonds between brands and users.

Knowit Experience offers competences in:

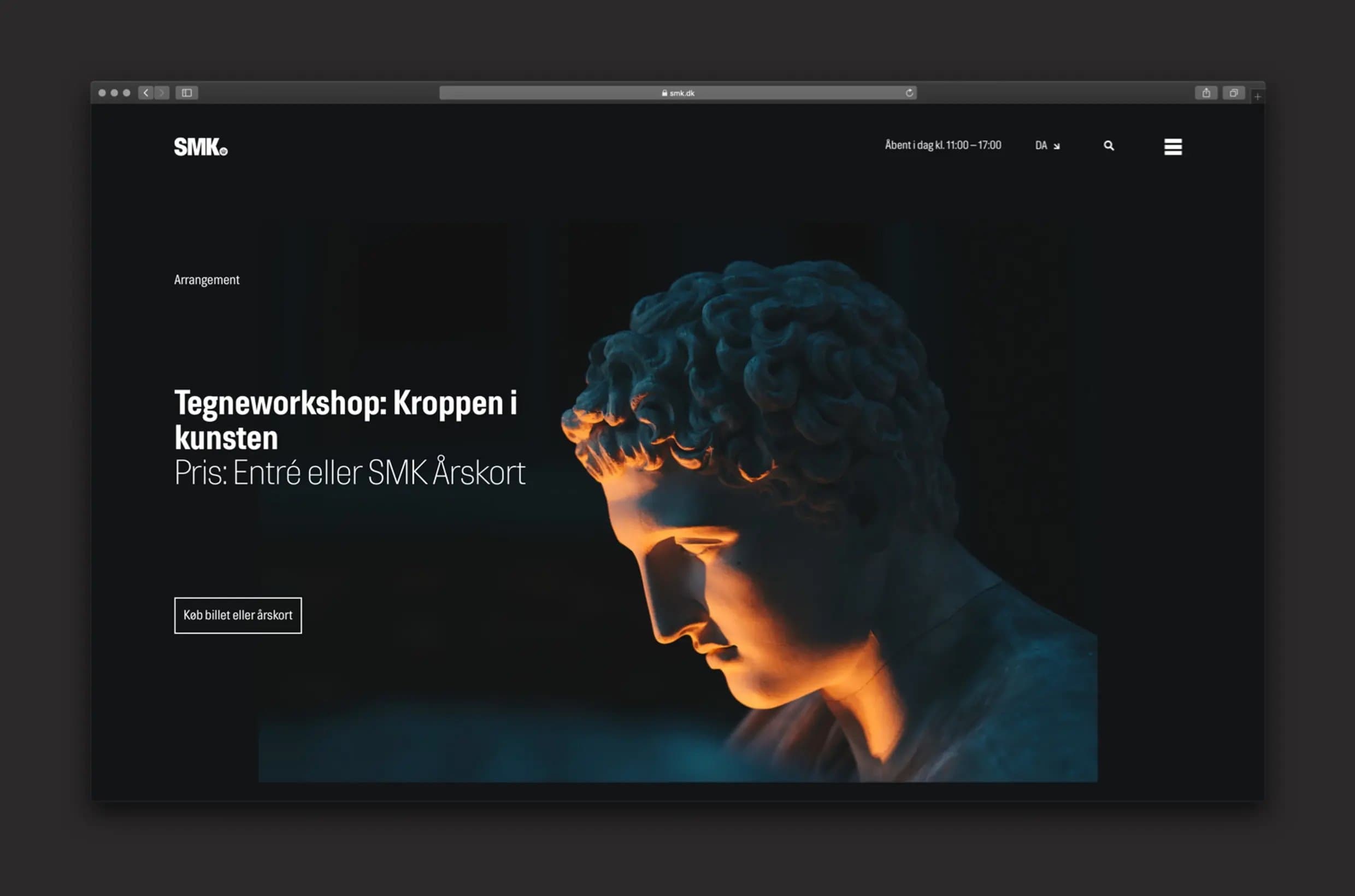

- Digital services and platforms for web and mobile

- Innovation and business growth

- Interactive design, service design, business design

- Digital commerce

- Brand strategy and visual identity

- Data-driven and automated marketing

Data-driven customer experiences for everyone

Our clients are found in all parts of society and a range of sectors – such as schools, healthcare, government authorities, e-commerce, transportation, and banking and finance. By creating a focused digital presence and unique user experiences online and in social media, we help each client achieve their business-critical goals and increase customer loyalty. Every day, thousands of people used the digital solutions that we create along with our clients.

As the largest digital agency in the Nordic region, Knowit Experience has competence extending from branding and design to data-driven e-commerce platforms. This means we help our clients transform their brands and create unique customer experiences.

Kenneth Gvein

Head of Knowit Experience.

Proudly presenting some of our work:

Be a part of our team!

Do you share our vision to create a sustainable and humane society through digitalization and innovation? Become a consultant, drive change, and help our Nordic clients create the future with the latest techniques.

900+

employees

Who creates unique user experiences that strengthen brand and customer relationships.

5

countries

We are located in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Poland.